CHAPTER 2 (PART 1)

STATIC AND DYNAMIC HARMONY

Introduction

In the last chapter, I introduced the concept of static and dynamic harmony and its importance in the construction of syntactic phrase structures. In this chapter, I will further explore the nature of static and dynamic harmony and explain how the form of these can vary according to the style and period in which the music was written.

In order to retain interest throughout their execution, all temporal art forms: music, the novel, theatre, cinema etc. Must vary their degree of tension and relaxation. When you watch a play or a film, observe how the tension varies, at one moment, static: scene setting, mood establishing, character introducing and then at another moment dynamic: something happens, tension is built up, what will happen next? The mood constantly alternates between these static and dynamic states. This is necessary to maintain the interest. These states are easy to identify once you know about them. They vary in length and in the degree of tension or relaxation but they are always there.

In music, these static and dynamic episodes are created by the use of different types of harmony. A prolongation of a single chord creates a sense of being stationary. I will refer to this as static harmony. Progressions of chords create a sense of moving forward. I will refer to this type of harmony as dynamic harmony. As well as varying the tension in music these episodes form the basic building blocks or syntactic elements that are necessary to make syntactic phrase structures similar to language sentence structures.

Static Harmony

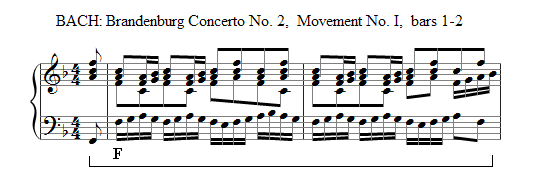

The simplest form of static harmony is the sustained tonic chord elaborated only by surface voice leading. In the following example, the tonic F chord is sustained for two bars:

The horizontal square bracket is used to show the extent of the tonic chord (F) and will be used to underline static harmony patterns. The tonic chord is elaborated by arpeggios, passing notes and auxiliary notes, but no new chords are introduced. The same chord may be sustained over several bars. The Prelude to Wagner's Rheingold is made up entirely of a sustained E-flat harmony which lasts for 136 bars. However, the most common type of static harmony is that made up of an oscillation between the tonic chord and other chords. Two commonly used chords for this purpose are the primary triads: chords IV and V, as follows:

I - [ IV ] - I

and

I - [ V ] - I

The square bracket will be used to indicate that a chord is used (in this case in conjunction with the tonic) to form static harmony. This type of chord will be referred to as an auxiliary chord by analogy with the auxiliary note. An auxiliary note is a non-harmony note that returns back to the harmony note. These are further discussed in the Voice Leading Appendix and Chapter 3 (part 2). These auxiliary chords do not create chord progressions since they return to the chord which precedes them. The example in Chapter 1. included chord V as an auxiliary chord.

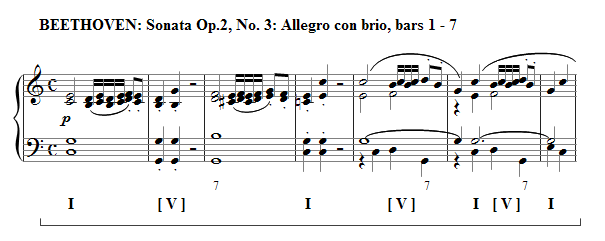

The following example also uses chord V as an auxiliary chord:

In this example the dominant auxiliary chords are deployed in root position and take on a role almost equal in importance to that of the tonic chord. This type of tonic-dominant oscillation is very common and is deployed in many well know melodies. The use of chord V, especially V7, as an auxiliary chord is a characteristic of classical secular music. The choice of auxiliary chord is thus an indicator of the style of the music. The extent of the static harmony is indicated by the horizontal square bracket and the auxiliary chords are show in square brackets. The figured base notation "7" is shown where a 7th is added to the dominant chord.

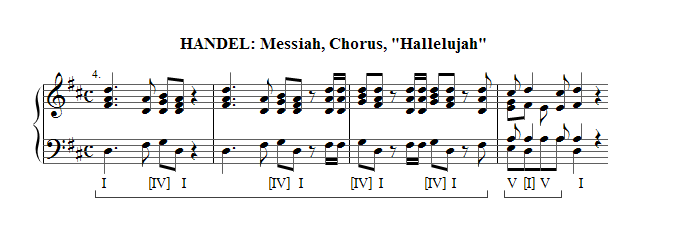

The following example uses chord IV as an auxiliary chord:

In this example the subdominant chords are also in root position. The 4th bar of the phrase is a brief prolongation of the dominant. The horizontal square brackets indicate the extent of the prolongations. Chord IV is frequently used in sacred music and is thus an indicator of the style of the music. Chord IV as an auxiliary chord is also common in popular music underlying one of its origins in gospel music which inherits its harmony from choral church music.

The purpose of auxiliary chords is to prolong the tonic (or sometimes the dominant) harmony. They do not create a forward moving chord progression. The static harmony normally occurs at the start of the phrase, introduces the melodic ideas (motives) and establishes the key at the start of the phrase. Chord V (especially V7 ) is more generally associated with secular music and chord IV (especially in root position) is more generally associated with sacred music, as indicated in the examples above. The choice of auxiliary chord thus contributes to the style of the music.

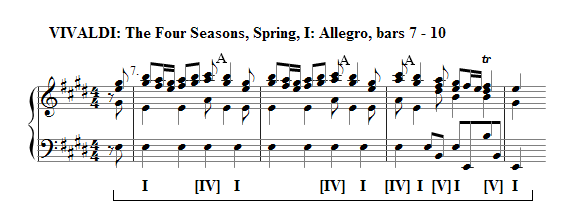

The following example demonstrates the use of both chord IV (not in root position) and V as auxiliary chords:

The appearance of the tonic chord in root position whilst the chord IV auxiliary chords are employed in second inversion emphasises the subordinate nature of the chord IV auxiliary chords in this example. In contrast, the two occurrences of the chord V are in root position, indicating the arrival of the cadence. The horizontal square bracket shows the extent of the static harmony. In this example, the static harmony encompasses the V - I cadence, and so, this brief phrase is made up of totally of static harmony. This topic will be further discussed in Chapter 6.

In this example, the IV chords could be interpreted as simply the result of auxiliary notes (shown in the examples by the letter "A") and not functional chords in their own right: the G# and B of the tonic chord ascending to form the A and C# of the subdominant chords at bars 7, 8 and 9 and return immediately to the G# and B.

There are thus two types of auxiliary chord:

a) Non-functional chords that arise merely as a result of auxiliary notes i.e. voice leading.

b) Functional chords ( in root position) These cannot be due purely to voice leading because of the movement of the bass to a new chord therefore they are structural in their own right.

In either case, theses chords create static harmony. The main difference is that the second type can take on further levels of voice leading elaboration.

The type of chord used for the auxiliary chord can also be an indicator of the period of the music.

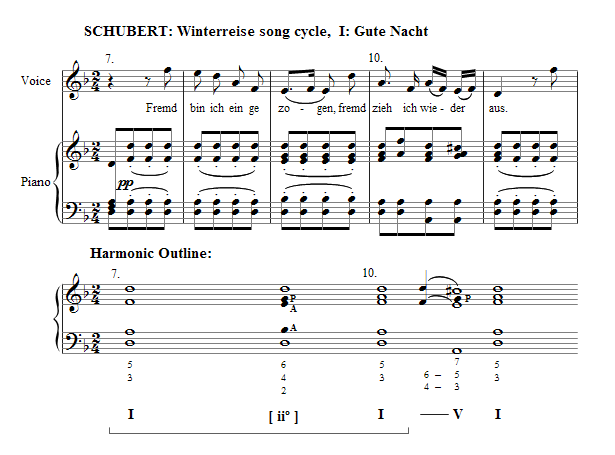

In the 19th century, harmonic possibilities are extended by the use of chords ii and VI as tonic prolonging auxiliary chords. In the following example, Schubert uses chord ii7 in the minor key:

Here, again, the static nature of the harmony is emphasised by the retention of the tonic note in the base. This is usually referred to as a tonic pedal. Note that since the ii7 chord arises as a result of the auxiliary and passing notes in the accompanying harmony, consequently the 7th of the chord is relieved of its normal obligation to resolve downward. As this piece is in the minor key chord ii is in fact a diminished chord (in this case with an added 7th) which is why this is shown as ii°. The auxiliary and passing notes are shown in the Harmonic Outline as "A" and "P". Pedal notes are frequently used under static harmony to underline the static nature of the chord succession. Pedal notes can be deployed under any auxiliary chords regardless of whether the tonic note forms a normal part of the auxiliary harmony. In the Harmonic outline, I've introduced some of the symbols to be used throughout this book and the Full Analysis Chapter to represent the underlying structure of the music. The structural notes are represented as white note heads and the voice leading as black note heads. The figured bass notation further documents the voice leading patterns. The cadential Chord V is elaborated by two appoggiaturas which create a cadential 6 4 chord (which is chord I in inversion) However, this is shown in the harmonic outline as black notes with tails (crotchets). This is to highlight the fact that they do not alter the underlying chord succession. Non-functional chords such as these will be explained in Chapter 3.

It can be seen from these examples, the choice of auxiliary chord in the static harmony contributes to the style and period of the piece of music.

The full book will contain further examples of static harmony from different periods of music.

The range of auxiliary chord possibilities can be further extended by the use of chromatic chords. The type of chromatic chord is a further indicator of style and period. Examples of these are given later in chapter 3.